Women and Violence in the World of Work

GAATW has long engaged with the issue of women's rights to mobility and work, and sees trafficking as an outcome of structural inequalities and a form of violence that undermines their enjoyment of these rights. We see and seek to support women workers organising and collectivising to tackle trafficking and other forms or exploitation. In our current work, we highlight stories of resistance of individuals and collectives in the process to raise awareness about the importance of organising, demonstrating and building solidarity among women workers. Working with different contributors from the media and workers’ rights organisations, we feature stories on gender-based violence in South Asia. We are focusing on supporting the rights of women (migrant) domestic workers, agricultural workers, and garment workers to organise and encourage collective bargaining with a view to ending both the structural violence and physical, psychological violence and harassment they experience in their everyday lives.

We worked with freelance journalist Raksha Kumar to produce the below stories of women garment and domestic workers in India, articulating the change they want to see in their families, communities and society in their own words.

Krishna Veni: 'Violence is not merely physical. Denying time off is equally oppressive'

Krishna Veni is a 37-year-old domestic worker in South Bangalore. She works as a domestic worker for ten hours every day. Her friends say they have never seen her without a smile on her face.

Krishna Veni tries to help her son in his homework. 'I have not studied formally', she says. But, she barely has time left after working at home and outside. 'Many days, I don't have time to eat at night', she smiles. Her work, both at home and outside, consumes her so much that she feels like a machine sometimes.

Krishna Veni has been working since the age of five. She feels everyone needs some days off from time to time. 'Even if only to return to work rejuvenated', she says. But the houses where she works have denied her leave very often. The only time she has taken time off is when she was unwell. 'Imagine if a corporate firm asked all the employees to come and work for 365 days', she says. Veni believes that being denied leave is also a form of violence in the workplace. She says she is striving hard to ensure that her children find jobs which have a balance.

Veni believes in collectives. She has been a part of a trade union for domestic workers for the past decade. She encourages her neighbours and colleagues to collectivise too. She holds meetings in her home to discuss problems at the workplace and hopes to find solutions together

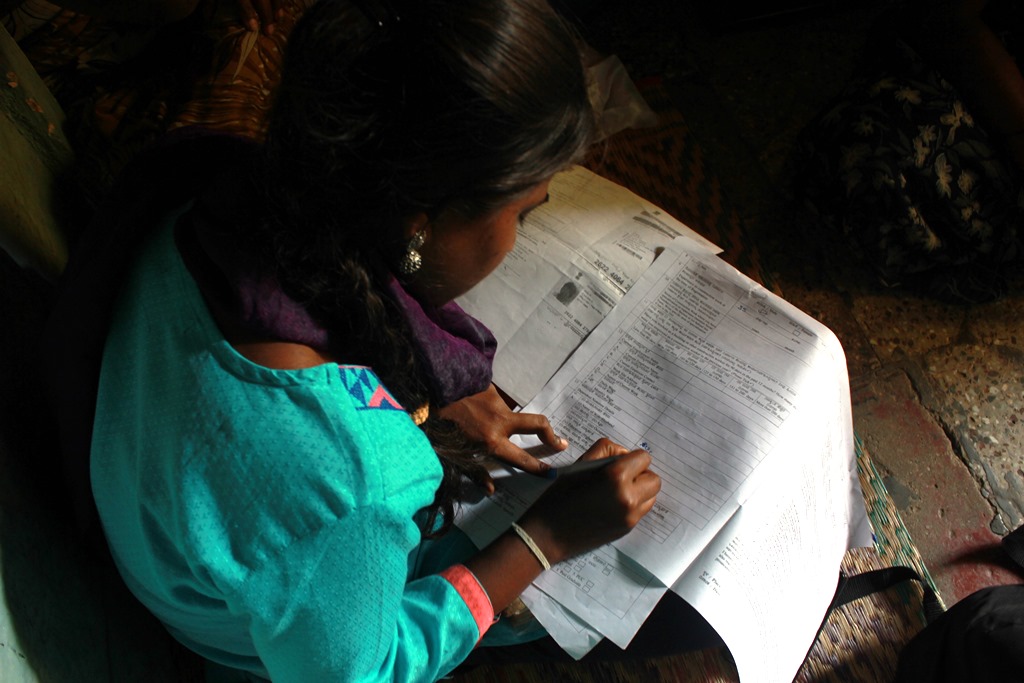

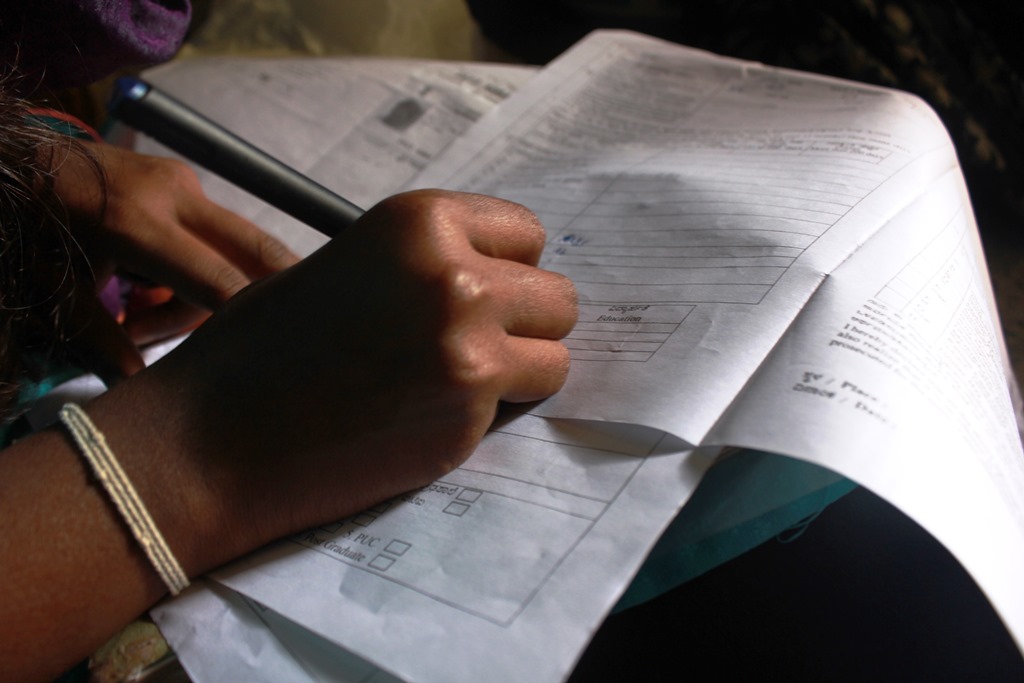

Veni's membership card for the Gruha Karmikara Hakkugala Union or the union to fight for the rights of domesmtic workers.

Veni's daughter Bhuvaneshwari studies in Class 7 in a local government school. Veni says without the violence in her workplace she could have done much more for her children. 'Given them a better future', she says. 'The cycle of violence ensures we remain poor and vulnerable', she says.

Veni works with union worker Radha Keerthana to register other domestic workers in the neighbourhood. There are more than 200 living in the area and about 70 are not registered yet.

Veni has a union card for every working member of her family.

Mari: 'Violence takes on various forms, especially when there are power dynamics'

My name is Mariyamma, but my friends call me 'mari', which means 'small' or 'tiny' in Kannada. They don't say it, but I know that the implication sometimes is that I am meek. Well, what can one do? Power has a place in our society and when we come from the less powerful sections we are forced to be meek.

I work as a domestic worker in six households. However, when asked about ‘violence in the workplace’ I can think of one particular house. I work in a Corporator’s house, he is a local politician. And is very influential in the Bangalore Municipal Corporation.

Until two days ago (mid-June 2018), I used to work in his house for more than four hours a day. Everything - including washing clothes, dishes and utensils, cleaning the massive house and its doors and windows - was all my responsibility. I did it diligently. Don't think I am patting myself on the back. The lady of the house was very happy with me. She used to call me diligent.

But, it took the whim of the Corporator’s son to banish me from work one day. Not sure why he did that. For all I know, he was in a bad mood. That made me realise the fragility of our employment. We work on the basis of trust, we develop bonds at a human level. Just like the one I had with the lady of the house. She was very good to me. But, we have no contract, no job guarantee, no second chance.

I live with my two sons. While one is a drop out, who does nothing but roams the streets, the other is mentally challenged. How do I sustain my life when there is no guarantee of employment whatsoever? If I have to define violence, this uncertainty would be it.

For ten years now, I have been a part of the Domestic Workers’ Union here in Bangalore. While it is amazing to find solidarity amongst fellow Union members, I think there is only so much they can do with each individual situation. Yes, collectivising helps. But, only to an extent.

I often sit up awake at night and wonder what my sons would do after I am gone.

(As told to Raksha Kumar. Edited for clarity.)

Dhanalakshmi: 'The union taught me how to work without fear'

Mayamma: 'Any organisation that teaches women their rights needs to be saluted'

A woman in her 30s was standing by the railway tracks on the outskirts of Bangalore in the early 1980s. She seemed to be shivering in the early morning chill. Only two years ago, she had delivered her third baby and seemed to be carrying another. 'I was not sure if she was going to kill herself or if she was looking to cross the tracks safely', said Jairam from the Garment and Textile Workers Union (GATWU).

It only took him one meeting with the woman to find out that she was no unassertive lady. Jairam managed to get Mayamma to join the union soon after.

Mayamma had a certain strength that not only managed to see her through bad times but helped the union as well. Since then she has been the backbone of the Bangalore chapter of GATWU.

'I managed to bring up five girls and a boy all by myself', she says proudly. 'Without any help from my husband or family.'

A migrant from a small village near Mandya town, Mayamma agreed to bear six children because, she says, she didn't want her husband to marry another woman for the want of a boy child.

Violence is something she was born with, she says. 'Each pregnancy was tough on me. There are no "child rooms" in garment factories'. The employees, mostly women, are expected to care for their children and meet very high production standards.

Situation in Mayamma’s house was worse because her husband did not help with caring for the children.

During the course of her decades long work in various garment factories, she has faced sexual violence, abuse and lack of pay. 'You name it!', she says.

Today, at 58, there is an accomplished smile on her face. 'I managed to raise all my kids, educate them and get them married off', she says. 'Today, I am a proud grandmother of four'.

However, according to Mayamma, none of this would have been possible without the support of a Union. 'Any organisation that teaches women their rights needs to be saluted', she says. 'Because we are brought up to believe we have none'.

Krishna, Veni, Dhanalakshmi, Mayamma and Mariyamma are working to make change in their own lives and communities. GAATW seeks to support them and women like them by engaging in the issue of violence in the world of work at the policy level, through the emerging ILO Instrument on Violence and Harassment in the World of Work, which is currently being negotiated. We see this as an opportunity to address violence and exploitation of women workers through an international instrument that addresses workplace abuses against women from a labour rights perspective, and to contribute to the development of a strong law at the international level that sets a baseline for taking action to eradicate violence and harassment in the world of work.

GAATW organised consultations with women workers groups in Sri Lanka and India in early 2018, and attended the International Labour Conference in June 2018 to support the inclusion of the rights of migrant, informal and domestic workers in the draft text. See our statement on the process published on International Workers Day.

What is "Structural Violence"?

We see a need to take a comprehensive view of violence. We see the systemic production of inequalities and violence through coercive work environments that lead to the denial of decent work as Structural violence in the world of work. In this we see physical violence and harassment as not separate from, but an outcome and amplifier of structural inequalities. Research by Action Aid has shown the strong links between physical violence against women and women's poverty.

Women in poverty are forced to stay in violent relationships, while "women who experience violence at the hands of an intimate partner often also have their behaviour controlled and are less likely to be able to find work".

While acknowledging the disproportionate impact of physical violence in the world of work on women, and the urgent need to address it, a Convention that limits its scope to physical violence and harassment will undermine our collective goal of advancing women's human rights, achieving gender equality and a just and equitable world of work. If this instrument is to be effective, it must address the structural roots of violence comprehensively and expose its embeddedness in neoliberal globalisation. It must address the forces that ignore, undervalue and criminalise work and livelihoods, and reinforce gendered wage inequalities and gender and racialised occupational segregation, and address the decent work deficit.

.pdf - Adobe Acrobat Pro 2_8_2021 4_36_32 PM.png)