Meet Our Members: Legal Resource Center for Gender Justice and Human Rights (LRC-KJHAM)

Legal Resources Center- Untuk Keadilan Jender Dan Hak Asasi Manusia (LRC-KJHAM) is a GAATW member in the city of Semarang, Central Java, Indonesia. Sumati Panikkar and Borislav Gerasimov from the GAATW-IS conducted this interview with Nur Laila Hafidhoh, Director, in October 2022 to better understand the organisation’s history, approach, and current programmes.

Borislav Gerasimov: Can you start by telling us what LRC-KJHAM means, when it was founded, and why?

Nur Laila Hafidhoh: LRC-KJHAM stands for Legal Resource Center for Gender Justice and Human Rights. It was born from a working group named KJHAM, or working group on gender justice and human rights, which was a part of the Foundation of Legal Aid (YLBHI LBH) Semarang. We were a part of this Foundation that focuses on gender justice and human rights. In the year 2000, the working group became an independent organisation, LRC-KJHAM. It started working on issues of gender justice and human rights like violence against women, migration, trafficking, and health rights. We provide legal aid, counselling, and group counselling to women who experience violence. The group counselling has now led to a survivors’ organisation support group.

We also conduct feminist research. We have a Feminist Participatory Action Research that we developed together with GAATW. There are programmes of FPAR with victims of trafficking, women migrant workers in Grobogan and Kendal in Central Java. We also organise communities of victims of gender-based violence, and of women migrant workers. We have two communities in the villages in Kendal and three organisations in three villages in Grobogan in central Java. In these two districts, the migration numbers are high. We also have some communities of rural women in Semarang. Some of them are victims of domestic violence, some of sexual violence.

We do policy advocacy at village, district, city and international level. At the village-level, it is regarding village regulations about protecting rights of women migrant workers, trafficking cases, and violence against women. We also advocate for regulations of programme and budgeting with the village-level government. Similarly, at the district and provincial level too, our focus is on protecting women from violence and exploitation, along with working with the criminal justice system. At the national level, together with other networks, we advocate for regulations on gender-based violence that Indonesia must adop; this happened just recently, in April 2022, when the government passed the Sexual Violence Crimes Law.

Sumati Panikkar: What are the communities that you focus on in your work?

NLH: Our primary focus is on women returnee migrant workers in Kendal and Grobogan. Our region is a major source of migration. Women have been migrating to countries like Saudi Arabia, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, etc. They have regular monthly meetings where they talk about migration, gender-based violence, and services for victims who approach the communities. Some of the members receive paralegal training and provide counselling and referral to victims of trafficking, gender-based violence, or violence during migration. Sometimes they refer to the village-level governments, who then may take some action like assistance with medical services. So, they document the cases that come to the community. Our community also advocates for policies in the village. For example, one community in a village in Kendal made a draft for village regulations on the issues of violence against women and trafficking and proposed the draft to the village government. The village parliament ratified this in 2019. Then there are economic empowerment activities like training to make products for small businesses and making economic cooperatives for products made from plastic waste.

|

A group of women migrant workers having a discussion in Grobogan |

BG: What are the main issues for which women migrant workers approach you?

NLH: The most common problem is sexual violence. As our research with GAATW showed, the women coming back from Saudi Arabia often reported sexual harassment and sexual violence. They migrate in the first place because of poverty. This poverty is related to natural resources. Earlier, they could depend on the produce from farms and fields, such as watermelon, melon, and tobacco. But climate change has affected that. Rain has become unpredictable. They can no longer depend on farm produce for their economic needs. They think that they can get more money if they go out of their village. Many women have been migrating to other countries in search of alternatives.

SP: What kind of work do the women do when they migrate to other countries?

NLH: Most of them work as domestic workers.

BG: What about issues related to working conditions abroad, like payment of wages and working hours?

NLH: Yes, they do face problems with wages, like not receiving wages for a long time. Physical and sexual violence, along with non-payment of wages, result in psychological stress and health issues . Physical abuse like being assaulted with hot irons by the employer is often reported.

BG: In such cases, what kind of legal support does LRC-KJHAM offer them? Do you file a case against the employers in the destination countries, or is it a case against recruiters in Indonesia?

NLH: Yes, the problem is also with the recruiters because they tell people that they will get a good salary and a good job. But after the recruitment process, they have to live in a place that is not good, not clean, there are problems with the food and so on. We investigate this and provide legal assistance. When there is a case from our district, we report the recruiter to the police. Often, the court does not take much action on the grounds that the recruiters did not force the workers. In some cases, the recruitment company changes its name and escapes legal action. It is easy for them to change their name and become untraceable.

SP: Are the migrant women returning due to Covid-19 or because of the other problems you mentioned? Has the return increased after Covid-19?

NLH: When we spoke to the community about the situation caused by Covid-19, they said that their family members and neighbours who now work as migrant workers are unable to come back to Indonesia due to Covid-19.

|

LRC-KJHAM conducting social awareness campaign on prevention of trafficking, in Banyuroto cillage, Magelang, Central Java. |

SP: You had mentioned that you work with victims of trafficking. Can you tell us a bit more about the situation of trafficking in your region?

NLH: In the country, we have some cases from East Nusa Tenggara. There was a case where 39 people were recruited by a company promising them good jobs in Malaysia. They were brought to Semarang from East Nusa Tenggara and were put in a dorm in bad condition. One of the victims escaped and contacted the police. LRC and the police investigated and reached this dormitory. Most of them were women and were brought to a government shelter. After investigation, the governments of the two provinces discussed how to repatriate the victims to their homes. Semarang is one of the transit areas for trafficking, along with Jakarta. Semarang is also a sending area, along with East Nusa Tenggara. Batam has also become a transit area.

Two days ago, we had a case of a woman victim of trafficking. She now lives in a shelter in Batam province. An organisation there contacted us to coordinate with the Central Java government, as the victim is from this region. Now, we are working with women’s organisations from the region to bring her back.

BG: You mentioned advocacy for budgets at the village level. Can you explain more about what your advocacy is regarding the budget? What changes are you trying to see in the budgets of the village level?

NLH: We organise community discussions about budgeting. We have a right to assess the budget from the perspective of women victims, women’s economic empowerment, case handling… In the village, there is a budget annually of 3-4 million Rupiah for handling cases of violence against women and for women and children victims of trafficking. At the district and provincial level, we make an analysis of gender-budgeting from the annual budget of the government.

From this analysis, we know that the part of the budget specific for women is very low. The budget for working on cases of violence against women, trafficking and migration is also low. Based on this, we organise dialogues with the government. After this process, the budget allotment for these has increased. But during Covid-19, the budget was redirected to Covid-19 protection.

Now there is also a regulation of the Ministry of Women Empowerment. There is budget for handling cases related to trafficking and violence against women in some provinces and districts. But the implementation does not include participation of civil society organisations like LRC. Sometimes we can report a case and get support for handling the case. But it is not much, and not all costs can be recovered from this.

SP: On your website, there is a mention of ‘Gender school’ and ‘Talking Girls’. Can you tell us more about these activities?

NLH: The Gender School is to enhance the capacity and knowledge of students and young people, help them learn about gender, women’s rights, and human rights. After understanding about human rights norms and concepts about gender, they learn how to respond to inequalities and injustice with some activities, like handling cases of violence against women. Everybody can be a partner of the victim - by receiving complaints, referring them to service-providing organisations, becoming peer counsellor, and campaigner by engaging in social media, sharing pictures, songs about human rights issues... They can also consolidate to become a union or a movement by getting together with other young people. Now, we are also trying to approach companies. After Indonesia ratified national law on sexual violence, companies also have to achieve a standard of zero tolerance on sexual violence.

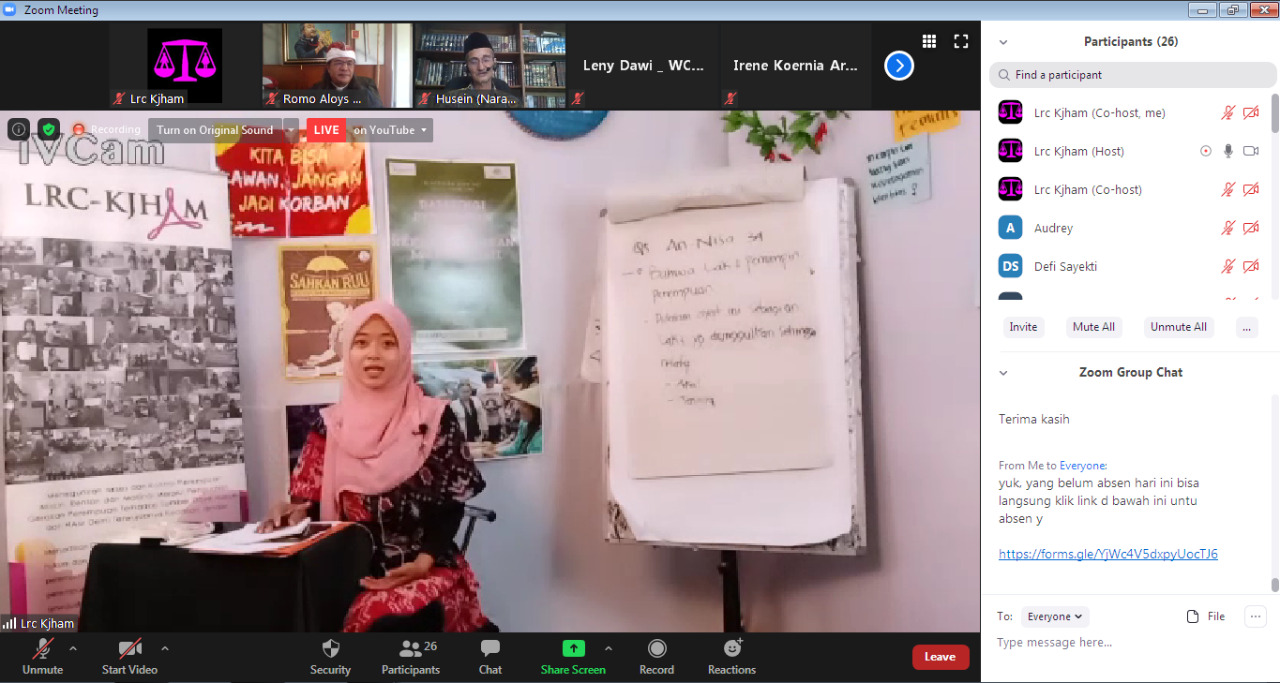

|

Gender School functions in both offline and online mode |

SP: Working on this wide range of issues over a period of two decades, you must be facing many challenges. Can you share what some of those challenges are?

NLH: One of the main challenges is money. The issue of funding is faced by many civil society organisations who provide services, especially if the programme is giving services like legal assistance. We have a strategy of attracting public donations but it is not enough. The other challenge is related to human resources. So, now we are trying to develop a system of volunteers.

BG: We don’t have more questions. Is there anything you'd like to add?

NLH: We have to develop a new strategy and approach on the issue of migration and trafficking. We need to refresh our knowledge. There is also a need to know more about the role of criminal justice system in the issue of migration and trafficking. We also need to focus on economic empowerment of returnee migrant women. These are a few things I feel we need to do in the future.

BG and SP: Thank you for taking time to speak to us.