In November, GAATW Secretariat spoke with Valeria, Operations Manager from Worker Support Centre (WSC), to learn more about how the organisation’s intensive grassroots outreach takes place in some of the UK’s most isolated rural areas, how workers’ lived experiences directly inform advocacy and policy change, and how trust-building, anonymity, and solidarity remain at the core of WSC’s work with migrant workers and local communities.

Vivian: Just to start, I wanted to know how and why was the Worker Support Centre founded? What was the context in which this organisation was started?

Valeria: Yes, so our director Caroline Robinson conducted research in 2021–2022 to understand the risks of human trafficking for forced labour in Scottish agriculture. At that time, post-Brexit, the UK was facing labour shortage, and as a result a new visa route was introduced: the Seasonal Workers Pilot. Initially, only a few thousand visas were available for workers to be recruited to come and work in seasonal agriculture in the UK for up to six months.

Over time, that visa scheme expanded, and there are now around 45,000 visas available each year for seasonal workers to come to the UK to support our food industry. However, despite this expansion, there was very little knowledge or research about their experiences. Of course, there had been previous schemes that facilitated migration to the UK for agricultural work, but what the research highlighted was that, despite many years of migrant workers coming to the UK, there had never been any study focusing on what they themselves thought about their experience. There was a clear absence of workers’ voices in the sector.

The Worker Support Centre was established to fill this gap, reach marginalised workers, to help prevent exploitation, and to ensure that workers’ voices finally became part of the conversation.

Vivian: That’s very interesting! Can you tell me more about how the centre started reaching out to these workers and what do you mean by marginalised workers? Which were those groups?

Valeria: The workers who come face very particular circumstances. In seasonal agriculture especially, workers come for a very short period of time because the visa is only for six months. They are recruited by a scheme operator, their sponsor, and then they are employed by farms. There is no language requirement for this visa, so most workers do not speak English. They are usually housed in caravans or porta cabins on farms. And these farms, particularly in Scotland, tend to be in very rural, isolated areas with sparse public transport and far from towns or cities.

As a result, most of the workers’ daily life takes place entirely on the farms. They spend the majority of their time working and are also housed there, but they have very limited opportunities to interact with local communities or to experience life in Scotland.

Workers from some farms are taken once a week by bus to do their weekly shopping; others have to find their own way to the nearest town or city, but these journeys are extremely challenging because, as I mentioned, public transport in rural Scotland is not very accessible. So that’s generally the context in which workers live.

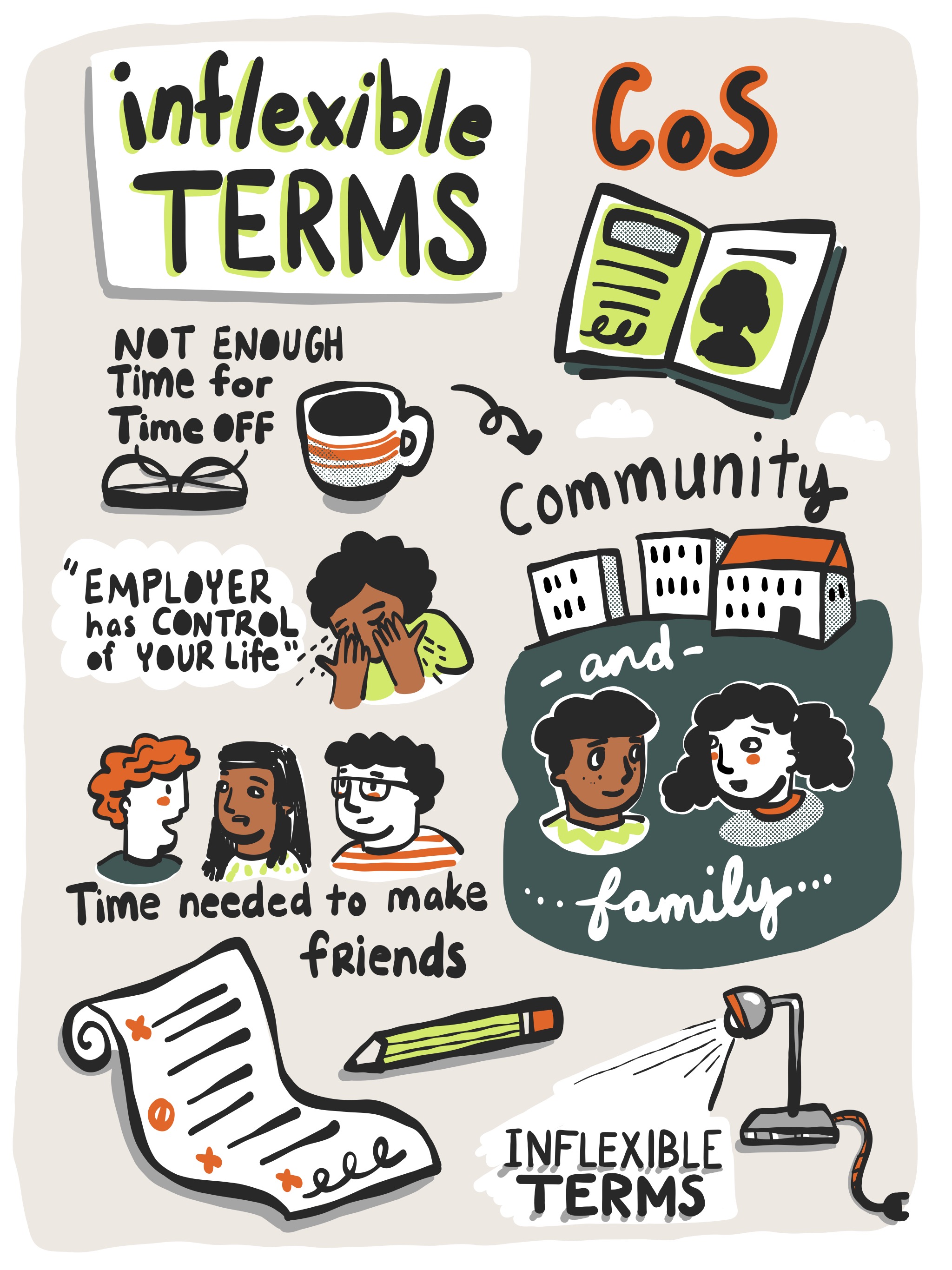

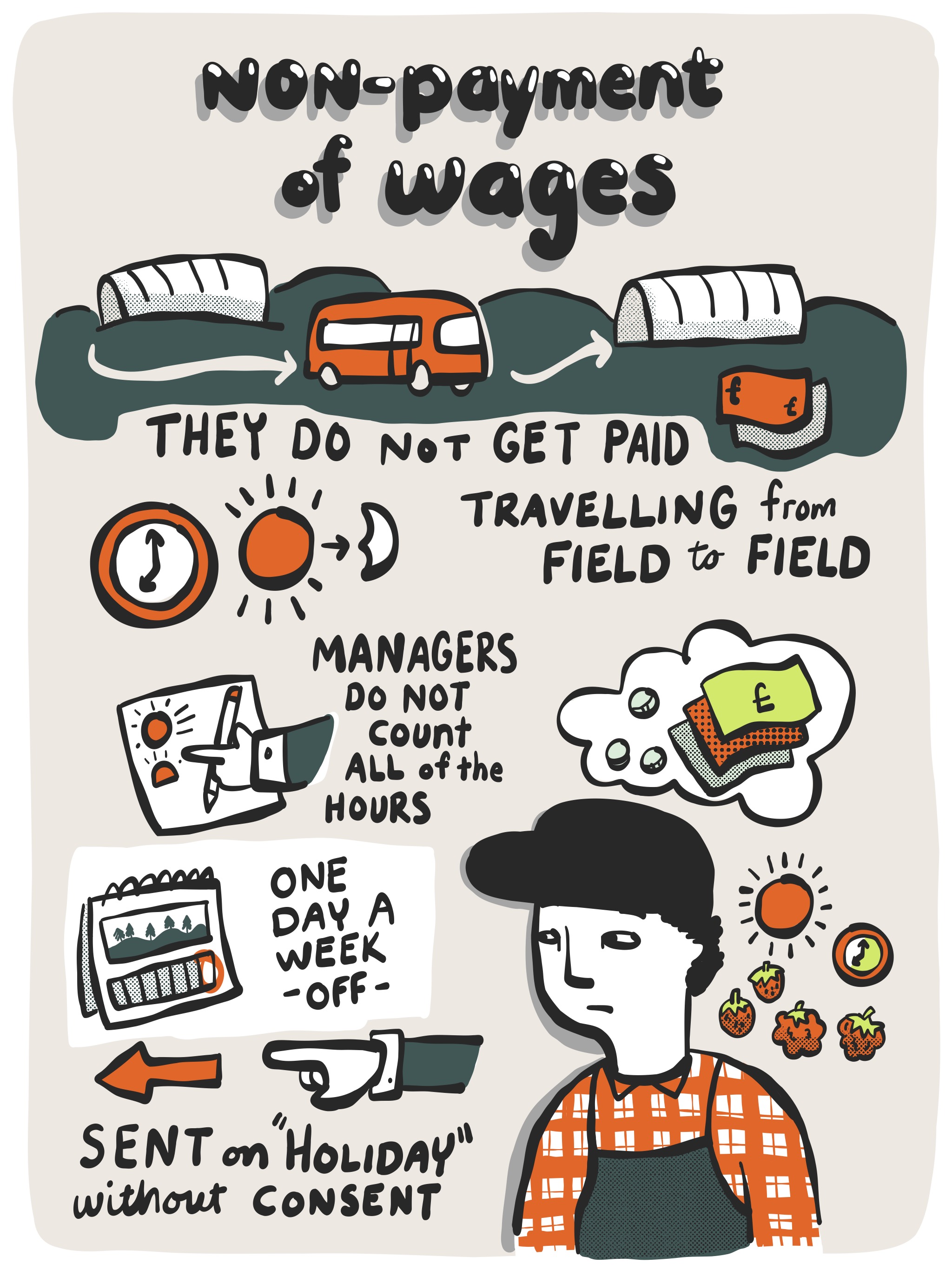

In addition to that, although the visa is for six months, many workers do not actually spend the full six months in the UK – it is often a bit shorter, and for some, it’s only a few months. Even within that short timeframe, they might be moved to two or three different farms because different crops are harvested at different times of the year across the UK. So workers who arrive earlier in the season might start picking daffodils, then be moved to strawberries, and then to broccoli. They spend only brief periods on each farm, which makes it even more difficult to form any connection with the local communities or the areas where they are placed.

All of this means that what happens on farms remains something that is not widely understood. The breaches of labour rights that occur and the issues that workers experience remain largely hidden because of the way the scheme is designed and the isolated environments where workers are placed.

That is why we reach out to workers. Actually, it started with my colleague Margarita. At the beginning, nobody really knew where these workers were, in the sense that there is no public registry showing their locations or the farms employing seasonal workers. This data isn’t even available to the Scottish government.

So we began by doing a lot of outreach, both online and in person. First, our in-person outreach, as it works now, involves going to places like car boot sales or standing outside major supermarkets near farms. We try to locate farms and understand where workers might go during their limited time off and when that time off usually is, so that we can meet them at specific moments – whether at bus stops, in shopping centres when those exist in bigger towns, or outside mosques. There are only a few mosques in the rural northeast of Scotland, but we know that for major celebrations workers will attend them, so we make sure to be present and share information about our work.

We also do intuitive online outreach, trying to figure out from reviews or comments online where workers might be living or spending time. And, I suppose, one key thing to add is that all of our staff have lived experience of the issues we work on. Our team members have worked in seasonal agriculture themselves and have a strong understanding of what happens on farms, when workers might be available, and how to reach them effectively.

Vivian: Wow, that is so strategic. It is actual field work.

Valeria: Yes, there is a lot of fieldwork involved. Last year, Margarita and Iryina even went on a road tour around the northeast, placing leaflets at bus stops near farms so that workers could see them. All of our materials (everything we use for outreach) is in the languages spoken by the workers. And yes, we now have many contacts who first connected with us simply because they happened to find one of our leaflets somewhere at some point.

Vivian: I was just wondering what you mean by reviews. From where, for example?

Valeria: Sometimes workers leave Google reviews for the farms, and when we see reviews written in Russian, Tajik, or Kyrgyz, for example, we know that the farm most likely employs seasonal workers. That helps us identify where to focus our outreach, either directly around that farm or nearby. We also try to understand where workers might go for their weekly shopping, because the big supermarkets in rural Scotland are limited and quite well known. Usually, there is just one within reasonable distance, so that becomes the most likely place for workers to go. There is a lot of this kind of research that takes place.

We’ve been working in agriculture for several years now. Going back to the beginning, we were initially set up as a project under the legal charity JustRight Scotland, and then we became a standalone organisation in 2023.

Most recently, we’ve begun working with workers in the health and social care sector, who are also on a tied visa, which is a different one from the agricultural visa, and one that tends to allow slightly longer stays. The modalities are similar but not identical. Again, we do a lot of in-person outreach by trying to connect with churches, leaving leaflets in shops, and standing near care homes. But because these workers are here longer term, they might have more opportunities to engage with local communities. So we are beginning to build strong links with churches and other community groups.

There is a lot of, as you mentioned, fieldwork and groundwork to make sure that workers know about us and the services we provide, and to begin building that connection and solidarity – both between us and the workers, and among workers themselves.

Vivian: Alright, I understand the rationale behind the Worker Support Centre. However, I would like to know more about the actual work that the centre does. After you reach out to workers, what services do you provide? What are your main focus areas when you engage with them? You mentioned that you share information with workers, but that they also share information with you. So what happens next?

Valeria: Yes, as I mentioned, we really work on prevention. Our work can be summarised through our five-step early exploitation prevention model.

First, we provide support. We ensure that people’s basic needs are met by helping them with issues they experience in the workplace and beyond. This happens through our casework services.

Second, we focus on literacy. We work with workers to make sure they understand their rights. We also gather evidence that can be used to enforce the law in ways that feel safe for them. Under these visa routes, there is a huge imbalance of power between employers and employees. In the health and social care visa, for example, the sponsor is the employer, which makes it extremely difficult for workers to raise any concerns. They fear losing their sponsorship, or that their sponsor might lose their license, which would mean the worker loses their right to be in the UK. So the risk of exploitation in this set-up is very high.

Third, we have our “Worker Power” work. We collaborate with workers to strengthen solidarity, build collective power, and support workers to shape fair workplaces. This includes building power not only within workplaces but also in policy spaces, ensuring that workers’ voices are present and at the forefront, where decisions are made about their lives. We also make sure they have the right connections with policymakers.

Fourth, there is the deterrence work. We partner with workers to ensure that labour market enforcement bodies meet their needs and help improve the overall processes for enforcing labour rights in the UK. We also escalate issues to enforcement bodies in ways that feel safe to workers, which usually means submitting anonymised evidence to report breaches in workplaces.

Finally, there is influence, which is our policy work. We partner with workers to develop policy solutions and to claim spaces for change. This is, again, about ensuring direct connections between workers and policymakers, so workers can speak directly to decision-makers about the issues they face and the policy recommendations they have.

That is, in a nutshell, the core of our work.

Vivian: Yes, I actually remember that Caroline shared in our past e-bulletin some of the workshops you’ve been doing with workers. I can’t recall all the details, but I remember there was a big white sheet where they were writing about their daily working life. For example, things like “go, caravan, faster”, things that employers usually tell them. How do you take those voices and incorporate them into your advocacy work or when engaging with policymakers for change?

Valeria: We have what we call our “Worker Power” meetings –– where we come together with workers. There is always a social element to it, so there might be food or an art activity, depending on the session. The idea is to bring workers together in a space where they feel comfortable.

In these sessions, we have conversations about the issues they experience, their priorities for change, and also explore how they think change can happen and what their role in that change could be, based on their preferences. We integrate all of this exploration with workers into our policy work and policy recommendations. We also organise meetings where workers sit with Members of the Scottish Parliament to share the recommendations they developed in these group settings and to highlight the issues they face on a daily basis. Most importantly, they share what they think should be done about these issues and how they believe things should change.

The risk that workers take in speaking out, connecting, and joining this work is significant, so they are very invested in seeing real answers and real change. And that, I think, is the core of what happens in this part of our work.

But we also have workers who want to engage in other ways – like writing articles for news outlets. For instance, over the summer, two workers engaged with us in many ways, including escalating issues on farms to enforcement bodies and attending Worker Power sessions. They were then keen to write an article, which was recently published in the Ethical Consumer magazine.

We’ve also had workers meet with two parliamentary committees of the Scottish Parliament recently. Illustrations were produced as part of that work and have been published on our website and social media, making sure their voices are shared in accessible ways, while fully ensuring their anonymity.

Workers may want to engage in many different ways. Some will write articles or speak to journalists while others might take videos of accommodation conditions, which can then be escalated to enforcement agencies to carry out inspections and improve conditions. Some bring other workers to sessions, helping to build connection and solidarity. Overall, there are many ways in which workers contribute to building solidarity, sharing information, and learning about their rights, which they share with others later on.

Recently, we’ve produced booklets on rights and entitlements, including information about pay. In agriculture, there is widespread wage theft, and these booklets provide a tool for workers to record their hours, ensuring the worker holds evidence if they wish to complain can be escalated or an anonymised complaint lodged about a farm’s practices. Sharing these booklets with other workers further strengthens solidarity.

So, there are many different ways in which this solidarity is built, depending on how workers want to contribute and the level of engagement they feel comfortable with.

Vivian: It’s sad that they have to take such precautions just to protect themselves, even for something like working, they need a booklet to track their hours and make sure their employers are paying them fairly. I remember Caroline also shared that. On the other hand, I’m amazed at how open the workers are to talking with the centre and even bringing other people in. As seasonal migrant workers, they face so many challenges, e.g. not speaking the language is just one of them. In that case, I would like to understand what are the biggest challenges in this work? I know time constraints are a major issue for workers, but what are the main challenges the centre faces, and how have you been able to overcome them?

Valeria: I think the biggest challenge is the significant fear among workers of being blacklisted or dismissed, and of not being able to return to the UK the following year if their connection with the Worker Support Centre becomes known, or if there are any issues reported in the workplace. This is certainly one of the key challenges we face as an organisation, because it prevents many workers from engaging with us. It also limits the potential for solidarity and collective action to develop.

The way we address these challenges is through trust-building. This is a continuous process and really forms the core of everything we do. We spend a lot of time building relationships with workers and ensuring that their engagement with us is safe. Every measure is taken to guarantee safety and anonymity, starting from not publicly sharing the location of sessions to timing media or social media coverage weeks after meetings so there is no connection to workers being away from the workplace. We go the extra mile to provide support and build worker power. For social care workers, this involves engaging over a long period of time, because trust takes time to establish. In agriculture, the short visa period means everything happens more quickly, but we maintain connections from one season to the next, even during the winter when workers have returned to their home countries. We welcome them back if they return to Scotland and continue building connections with new and returning workers.

In all our work (whether casework, worker power, or deterrence work) the workers’ voices are always at the centre. We never take action without the full discussion, agreement, and consent of the workers involved. Our staff also speak the languages of workers and have similar lived experiences, which helps us connect, but we recognise that trust-building is ongoing. Once trust is established with some individuals, it can gradually extend to others.

There are additional challenges linked to the structure of the visa system and the nature of the work. In agriculture, the short-term nature of the visa limits the time workers have to engage in anything outside work. In social care, the combination of employers acting as sponsors and long working hours makes private life extremely limited. Social care workers may be out early in the morning until late at night, travelling between clients, often with only part of their time paid. This leaves very little time to cook, sleep, or engage in anything outside work.

Because of these factors, the risks of escalating issues or joining collective action are very real, and the limited free time makes engagement challenging. Workers’ issues are often extremely acute, with significant impacts on mental and physical health, which means they are understandably focused on resolving immediate problems.

What we try to do is bring workers experiencing similar issues together to explore collective solutions. So yes, these fears, time constraints, and the acute nature of the issues workers face are some of the biggest challenges for us.

Trinity: Thank you, Valeria. I was wondering if they’re often returning migrants? Do they come multiple times? I would imagine that if they are only coming for one summer, or one period of time, it would really make it much harder for them to be self-advocates. They’re just acclimatising to the changes and the environment, and they don’t really have the time to know what to do.

Valeria: Yes, some workers do return. The seasonal worker visa hasbeen inplace for a number of years, so some workers have come twice or even three times. Sometimes, it could be their second or third year. Definitely, both farms and scheme operators tend to prefer returning workers.

But we also know that workers who raise issues can be prevented from coming back, which is one of the major challenges. That’s why ensuring anonymity is so important because blacklisting does happen. We know of workers who raised even minor issues in previous years and were not invited back. This clearly discourages workers from escalating problems with farms, recruiters, or scheme operators, and ultimately, from engaging with us.

That’s why we focus on strategies that guarantee their safety and anonymity while still enabling collective action, because the issues workers face are severe. It’s also why it’s so important for workers who already know us and have built trust to bring other workers along. This helps new workers feel supported, connected, and reassured that help is available if they need it.

Trinity: And is there any sign of potential changes that could reduce blacklisting? For example, by making the visa less dependent on employers? Is anything like that currently being considered or in the works?

Valeria: Unfortunately there isn’t much willingness to examine the risks that come from this dependency, hence the risks inherent in tied and restrictive visas in general.

The visa also includes the no recourse to public funds provision, which means workers can’t access public funds in the UK if they find themselves in a difficult situation. This adds another layer of reluctance to make any changes. But, of course, as independent NGOs and worker-led organisations, we are strongly pushing for policy change.

Trinity: Yeah, it’s really complex to think about how little attention is being paid to their needs in that system. With the scheme operators, I know that in other countries, sometimes migrants looking for work have to pay to be matched with employers. Is that part of this system as well? Do they have to essentially buy in to get a job?

Valeria: The official costs are only the visa and travel. However, we do know that workers in some countries end up paying illegal fees in order to enter the scheme. Officially, they make it clear that this shouldn’t be happening, and the fees should only cover the visa and travel costs.

Vivian: Right, thank you, Trinity and Valeria. Caroline has already been collaborating with GAATW for a long time and has been part of the advisory committee for Labour Rights, but the Worker Support Centre has basically just joined GAATW as a formal member. I would like to know, what do you, or your team, expect from this experience? What would strengthen the work that you do by being a member of GAATW?

Valeria: To me there are two key elements.

The first element is learning. Learning from organisations that are working in similar or very different contexts, learning from their strategies, their experiences, and how they engage workers in contexts where that engagement is extremely challenging. This teaches us so many lessons on how we can do things differently, better, and more creatively in our own context. Having that learning in the background, that connection with the rest of the world and with organisations that are doing it well, is extremely important to us. That’s something we really value. The Worker Support Centre was also created based on best practices from organisations around the world, from other worker centres globally.

Part of that first element is also about resources that have been created in other contexts and how we can use them. But we also know we can’t remain static. We need to have conversations that push us forward, and to do that, you need different points of view while still having these conversations in a space where everyone agrees on certain key values. To us, that is really meaningful.

The second element is about connections with countries of origin of the workers here, and thinking about how we can build on that connection to do work in the countries where workers come from, even before they travel to the UK and Scotland.

Vivian: Right, I think most of our members see that as a strength, i.e. connecting origin countries to destination countries, whether for labour rights, migrants in general, or trafficked persons, for example, in the assistance of women specifically. Thank you so much. Would you like to add anything about what the Worker Support Centre is planning for the future, any upcoming work or projects you would like to share with us?

Valeria: Yes, I suppose one of our key objectives going forward is to strengthen the connection between workers and communities, and communities’ connection with workers. We’ll be putting a lot of effort into making workers more visible among communities that are close to the farms or in the places where our elderly are cared for – bridging that connection.

We also want to ensure that we begin to build solidarity not only between and across workers, but also with local communities, which is really key and something workers have highlighted as one of their main interests.

Vivian: Thank you so much, Valeria, for sharing insights into the work of the Worker Support Centre. It’s inspiring to hear how your team supports workers, builds trust, and fosters solidarity with communities. We look forward to seeing how your future initiatives continue to create meaningful change!